Fetching Data from Web with HTTP GET requests

When you open a browser, enters an URL, and hit Enter your browser issues a so-called HTTP GET request to a server pointed by the URL. The server reacts to the response taking into account who sends it and with which parameters, then responds back with data. In casual use, that data is often a plain text formatted with special tags known as HTML:

<html>

<head>

<title>I’m a title shown in tab</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Hello, I’m a heading</h1>

<p>I’m a paragraph that a user can read</p>

<p>I’m the second paragraph</p>

<p>A browser knows how to render me pretty</p>

</body>

</html>

HTML is nice to present a page intended for consumption by a human reader, but it’s not the only variant how the server can reply. There are many possible response formats, and some of them are intended to be consumed by a machine, not a human. JSON is a simple and popular format to be consumed by devices. Try to open the following URL: http://api.xod.io/httpbin/ip

The server responds back with an IP address of a requester (you) as it seemed from the outside world.

{ "origin": "185.36.157.186" }

The response is not so aesthetically pleasing, but it would be easy for a machine to parse it and do something useful.

XOD provides nodes to make HTTP requests and parse responses. As an example, let’s make a XOD program that requests an external IP address and shows it on an LCD.

We need an established internet connection for the device to go on. How to make it depends on the module you use as the internet provider. Refer to Connecting W5500 for an example of connecting an Ethernet Shield board.

From now on, we expect you’ve created a node named internet encapsulating your internet connection.

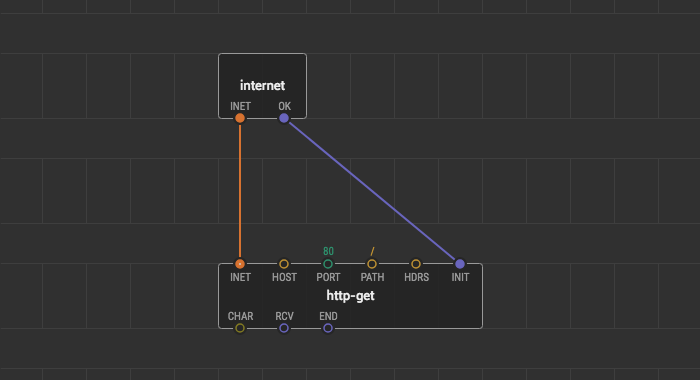

Sending request #

The first thing to do is sending the request. The process involves opening a TCP connection to the internet server and writing request bytes in a proper format defined by the HTTP protocol. These details are encapsulated inside the xod/net/http-get node, so it is enough to specify only basic details of the request.

The INET input pin should be linked to the node providing an established internet connection. The INIT input pulse starts a new request/response session. The rest of the inputs specify a URL and request payload.

To understand which input means what, let’s look at parts of an URL:

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| http | :// | example.com:8080 | /foo/bar?baz=42&qux=hello |

- The part before

://defines a scheme. For the HTTP protocol it is eitherhttporhttps. The latter is secure HTTP protecting you from an evil traffic interception or injection. Note, that HTTPS relies on heavy cryptographic algorithms which might be unsupported by your hardware. - The next part is called host which is a server domain name and the destination port split by a colon. A web server may listen on many ports with completely different sites and services on each of them, but conventionally HTTP servers prefer port 80 whereas HTTPS prefer 443. If the port matches the default, the port part can be omitted:

http://example.comandhttp://example.com:80are the same thing. - The tail starting with a forward slash is called path. A few decades ago it was used as a file path to be returned by the server. But now in most cases, it is an arbitrary string which points to a virtual resource known as endpoint to be returned. The convention of using slashes to structure the path was preserved though. At sometimes you’ll see an extra key-value component after a

?. It’s known as query arguments, but nevertheless, it is just another part of the path.

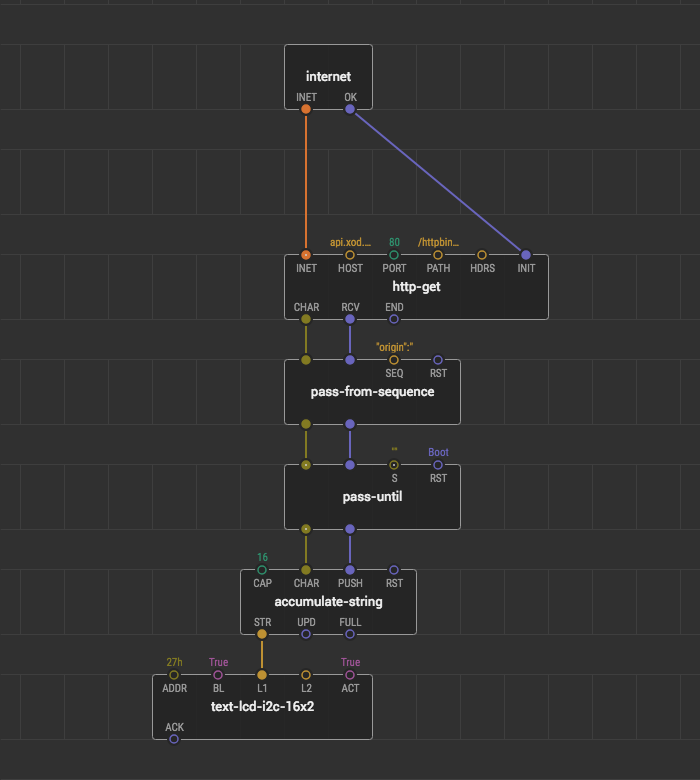

We are going to make a request to http://api.xod.io/httpbin/ip and now you are ready to fill in the address details:

HOST="api.xod.io"PORT=80PATH="/httpbin/ip"

One more input to note is HDRS which defines so-called HTTP headers which are sent along with the request. The headers can tell a server to adjust its response to be more efficient or easy to consume by a client. Headers are also used for authentication purposes. For our example they are not necessary, so leave the input blank.

Now, if you upload the program to a board, it will make a single HTTP request to the server, the server will see it and reply. Currently, we’re ignoring the response. Let’s fix it and make something useful with the incoming data.

Parsing response #

The http-get node has several output pins through which it pushes the response character by character and then notifies that the response is completed.

Powerful computers usually read an HTTP response entirely into memory and then pass the buffer to a processing function. However, that’s not always possible for microcontrollers having a few kilobytes of RAM. To be efficient in terms of consumed memory we are going to use a stream parsing technique when the incoming data is processed on the fly as it goes in.

Take a look at a sample response again:

{ "origin": "185.36.157.186" }

We are interested in the “185.36.157.186” part. The rest can be safely ignored. Our plan is:

- Skip all characters until a sequence

"origin":"is found - Accumulate all characters until another

"is found - Use the accumulated string as the result

You can find nodes for the basic streaming processing in the xod/stream library. We will use pass-from-sequence, accumulate-string, and pass-until.

The metod described above is only suitable for extracting a single value from a small response. Check out Reading JSON Data to learn how to handle more complex cases.

Putting all things together, here is the patch to print the external IP address of your IoT device on an LCD:

Although the result might seem not very expressive, it demonstrates one full cycle of interaction with a server located on the internet. To request some exciting data you need to find a public web-service with an HTTP API endpoint providing the values you are looking for. The principle of the communication will be the same for any other server.

In cases when your device should affect the outside world, it is often required to use HTTP POST requests instead of HTTP GET. In these applications use xod/net/http-post instead of http-get which slightly adjusts the data sent over the network. The rest of the details is the same as shown in this article.